The History of Japanese American Farm Labor Camps

Executive Order 9066

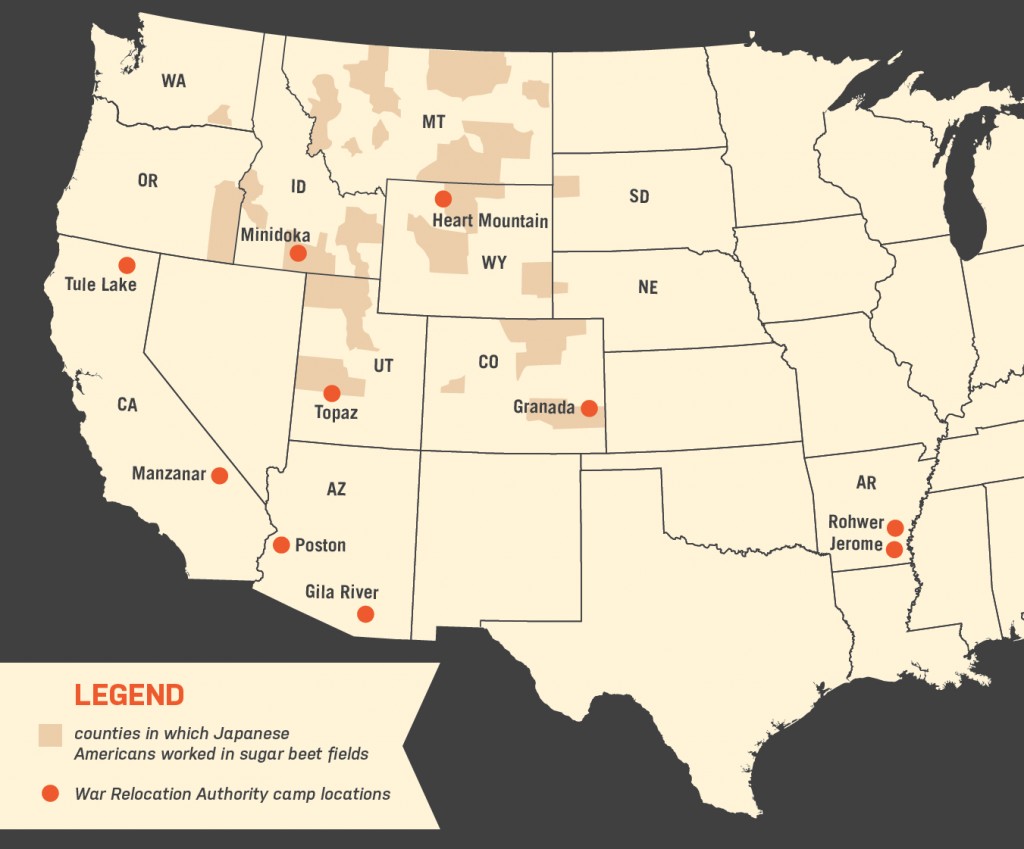

During a period of extreme paranoia and heightened racism following the attack on Pearl Harbor by Japanese warplanes, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. It authorized the forced removal and incarceration of more than 120,000 U.S. residents of Japanese ancestry (Nikkei)–nearly two-thirds U.S. citizens–from the West Coast to concentration camps. Between 1942 and 1944, some 33,000 individual contracts were issued for seasonal farm labor, with many working in the sugar beet industry. This exhibit introduces their story.

The Need for Sugar

Sugar was a vital wartime commodity. In addition to food use, sugar beets were converted to industrial alcohol and used in the manufacturing of munitions and synthetic rubber. In 1943, the United States Beet Sugar Association declared that every time a sixteen-inch gun was fired, one-fifth of an acre of sugar beets went up in smoke. With imported sugar from the Philippines restricted due to the war with Japan, the federal government lifted growing restrictions on sugar beets, increasing acreage by 25 percent. Demand soared for seasonal laborers to cultivate and harvest the sugar beets. Sugar companies, farmers, and state and local officials in western states clamored for the use of Japanese Americans to replace workers who had departed for wartime industrial jobs or military service.

The Oregon Plan

The War Relocation Authority (WRA), the federal agency created to handle the incarceration, had considered establishing labor camps in the spring of 1942. The idea was rejected, however, because the agency feared anti-Japanese sentiments would lead to violence in communities slated to receive Nikkei laborers. Some states devised their own plans to relocate Japanese Americans to work in sugar beet fields. The so-called Oregon Plan, developed by Governor Charles Sprague’s executive secretary George Aiken, sought to move the state’s 4,000 Nikkei to abandoned Civilian Conservation Corps camps in three eastern Oregon counties to work in agriculture and on public works projects. Though ultimately rejected by the WRA, the Oregon Plan did result in the establishment of the first Japanese American farm labor camp in Nyssa, Oregon. This marked the beginning of the WRA’s seasonal leave program.

The Seasonal Leave Program

To address the serious shortage of farm laborers, the seasonal leave program allowed Japanese Americans to leave assembly centers and concentration camps for agricultural work. To participate in the program, state and local officials had to provide assurances: officials would maintain order and guarantee the safety of the laborers, labor would be voluntary, imported labor would not compete with local labor, and employers would pay prevailing wages and provide housing and transportation. The farm labor program was a precursor to the WRA’s larger resettlement program, which sought to relocate Nikkei away from the concentration camps and into the interior of the United States.

Japanese Americans left the WRA detention camps for seasonal farm labor for several reasons: the ability to earn better wages–agricultural laborers could earn more in a few days’ time than in a month working in the camps; the opportunity to escape armed guards and barbed wire; and a chance to contribute to the war effort. More than 45 percent of West Coast Nikkei already had experience in agricultural work before the war.

The Program’s End

The seasonal leave program ended in 1944. More than half of seasonal labor participants were able to convert their work into indefinite leave from the concentration camps. During the course of three years, Japanese American farm laborers helped cultivate and harvest thousands of acres of sugar beets in western states. They are credited with saving an estimated one-fifth of the area’s sugar beet acreage. Their story is a small but vital chapter in World War II history.

The Photographer: Russell Lee

This exhibit features a selection of photographs from Russell Lee’s documentation of Japanese American farm labor camps near the towns of Nyssa, Oregon and Rupert, Shelley, and Twin Falls, Idaho. A photographer for the Farm Security Administration (FSA), Lee captured nearly six hundred images of the Nikkei wartime experience. From 1935 to 1944, the Historical Section of the FSA’s Division of Information oversaw a documentary photography program that produced approximately 175,000 black-and-white film negatives and 1,600 color images.